Image 1 of 4

Image 1 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 2 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Mark Kelner: Solaris, Artist Monograph, 2018

Published in tandem with the opening of Current Books at Studio Two Three in Richmond, Virginia, this 16 page project-specific monograph, (the artist’s first), features 30 full color images and an essay by Mark Kelner. Printed in an edition of only 200 copies, this catalog is being sold exclusively here. An excerpt from Solaris is below:

There’s never been a time when I wasn’t collecting... something. Baseball cards, Star Wars figures, Smurfs, Kennedy half-dollar pieces—all were the subject of substantial, deeply felt, slightly random assemblages begun and ended before I was 12. At 13, I got into posters and that was that. At 23, newly minted in Los Angeles with a job ‘close’ to the movie business, I became a weekend dealer of movie posters.

American poster designers such as Saul Bass and Jacques Kapralik, Frenchmen Jean-Michel Folon and Boris Grinsson, Italians Ercole Brini and Ermanno Iaia, among others, framed a new way of looking at art and film and the relationship between the two. But it was a MoMA exhibition catalog of the work of brothers Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg that introduced me to the use of non-objective forms, Constructivism, the Russian avant-garde, all serving a writer’s script and a director’s vision. For me, life expanded.

My personal history with paper, ephemera, and memorabilia is also tied up in my connection to the Soviet Union. I was conceived in Moscow, but born in Ohio. That duality has often become the subject of my work as a visual artist—one foot in each of two very different worlds, two very different streams of history.

In many ways, the very definition of what a poster is and could be was utilized masterfully by the Bolsheviks. They recognized the poster as both an iconic weapon of power and as a traveling propaganda tool.

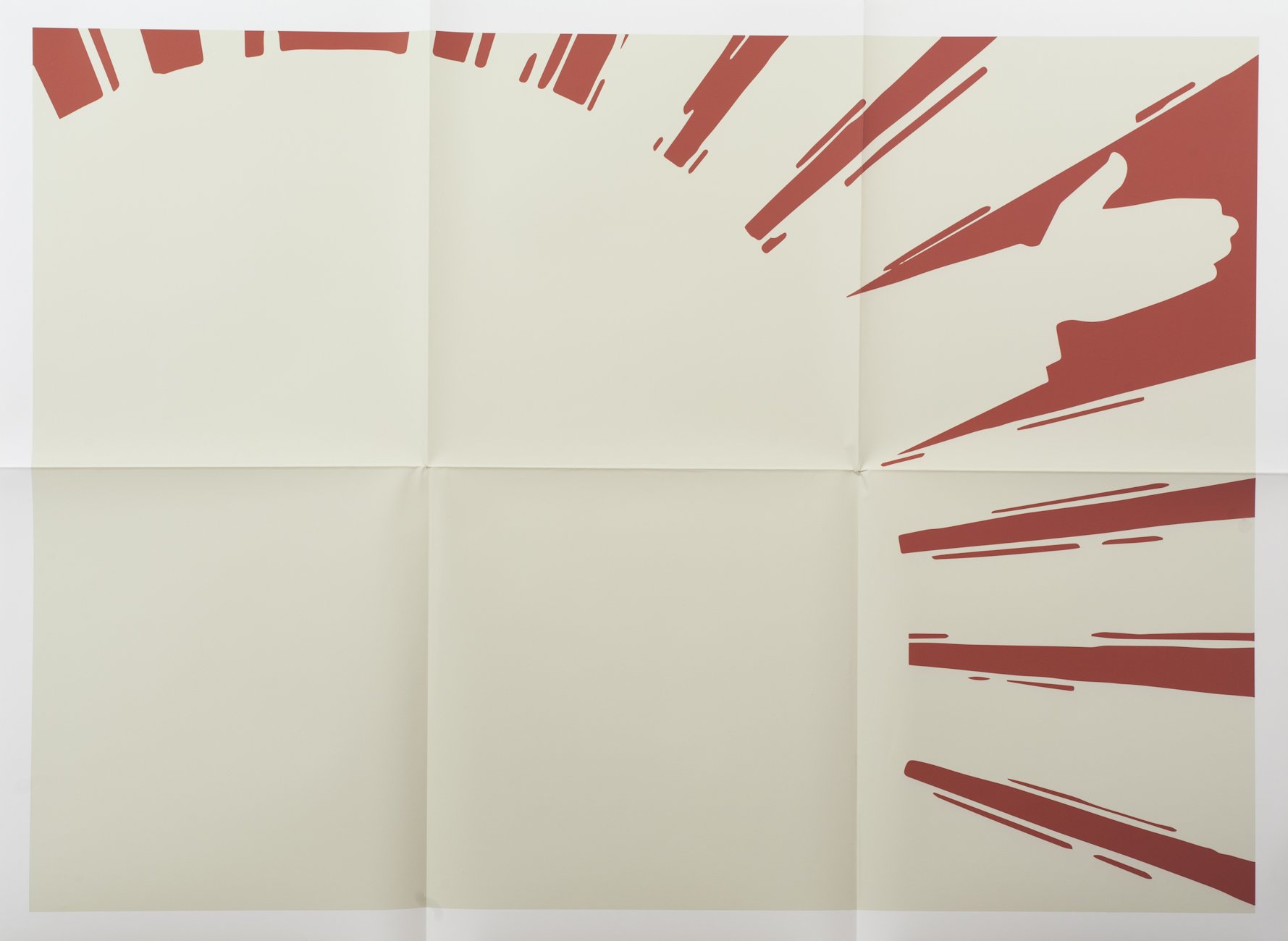

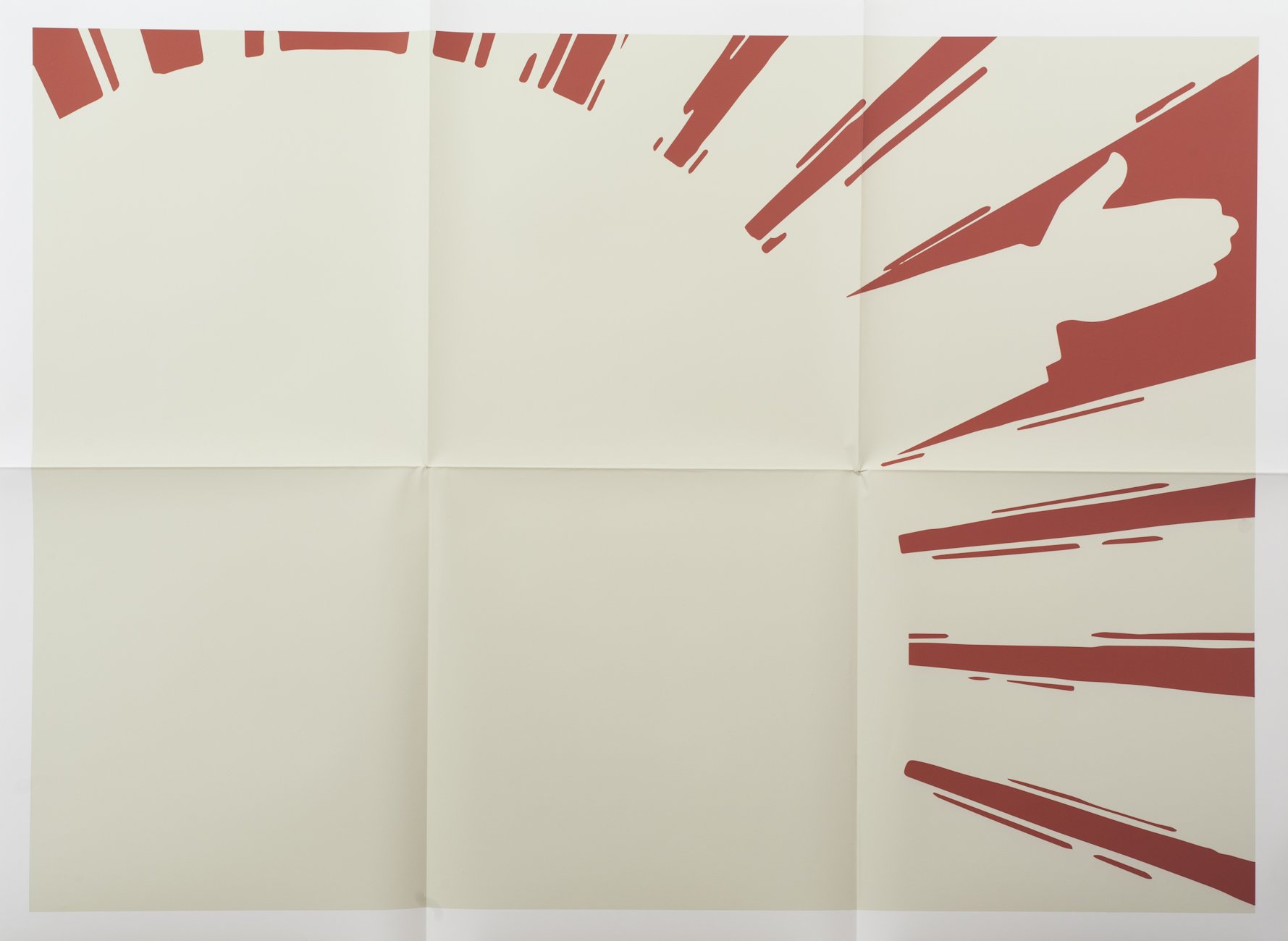

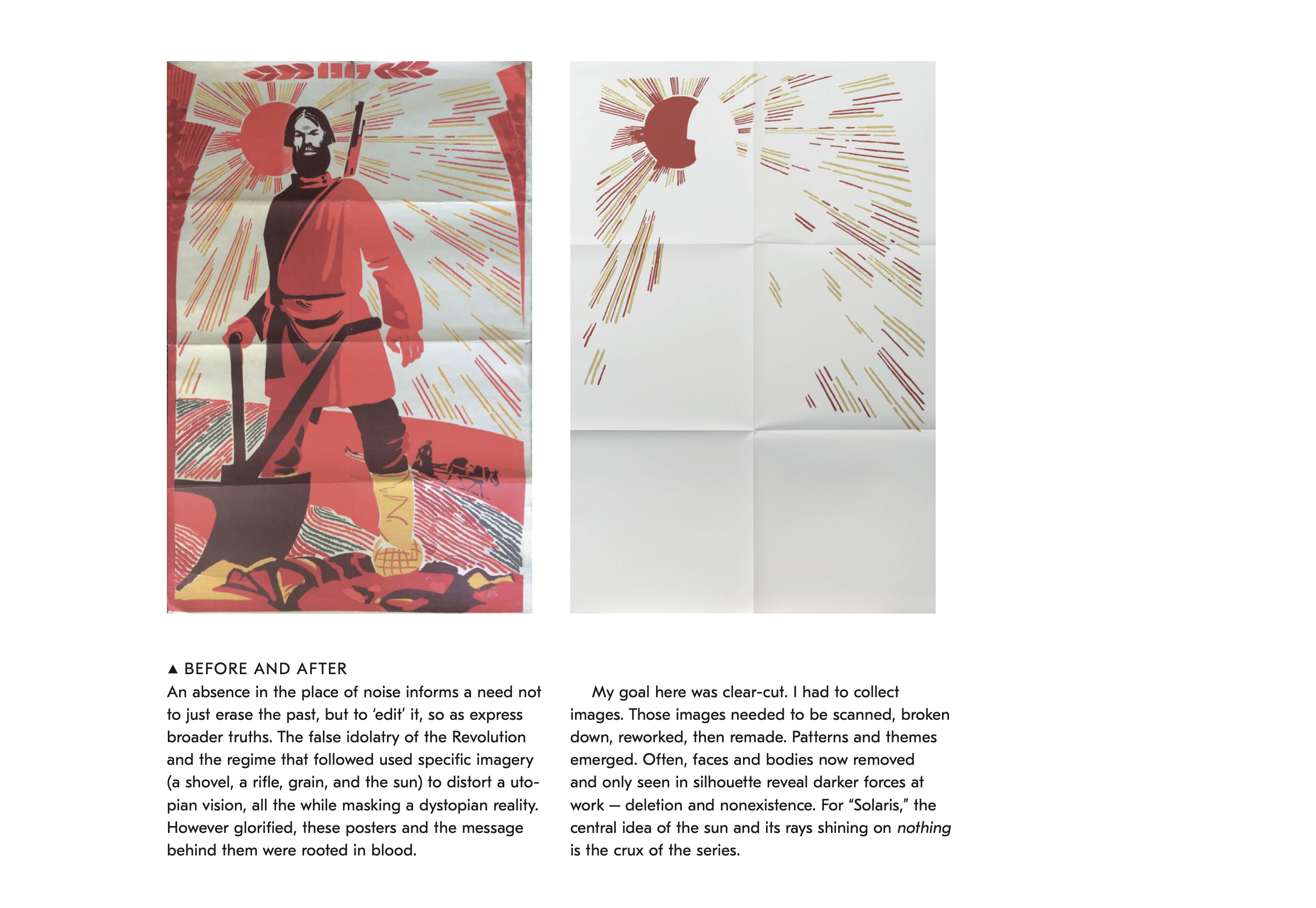

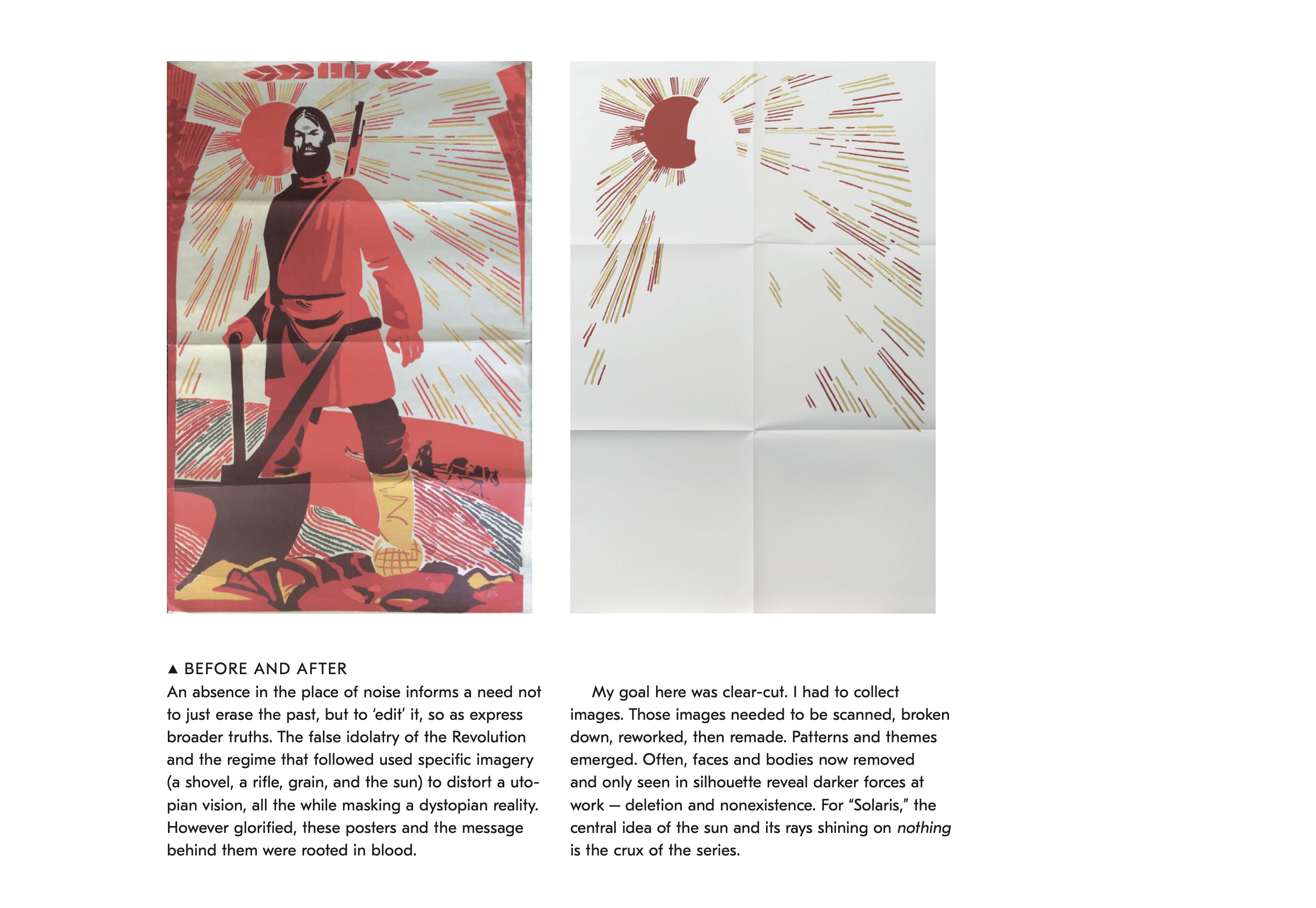

By repurposing well-known and rare Soviet posters, Solaris attempts to evoke a very specific and simple metaphor: that among the many false representations of his failed revolution, Lenin promised the sun and everything under it—and delivered nothing.

Later, the Communists perfected the art of agitating mass culture by means of multiplying their message. All art had to serve the State and the ideal of their utopia was symbolized by remaking the sun (and its worship) into a logo of sorts. By removing almost all figurative elements, all traces of text, all which is ‘happy’, all that is left are empty, minimal, and absent images. These new works evoke a sense of ambivalence and incongruity, something unfin- ished, and something unsaid.

Moreover, 2017 marked the centennial of Russia’s October Revolution and it just felt ‘timely’ to embark on a series that touches on themes of violence, migration, displacement, disinformation—all the while ironically seeming pretty to look at and ready-to-hang.

As a collector, I lost count of the tens of thousands of posters that were considered as possible raw material for the project. Concerning the assemblage presented in these pages, I’m especially struck by the objectification and commodification of an ideology, which 100 years removed, now becomes a decorative thing to put on one’s wall. There’s a contemporary antiquity to it all. At the same time, there’s an uneasy recognition of history repeating itself.

Published in tandem with the opening of Current Books at Studio Two Three in Richmond, Virginia, this 16 page project-specific monograph, (the artist’s first), features 30 full color images and an essay by Mark Kelner. Printed in an edition of only 200 copies, this catalog is being sold exclusively here. An excerpt from Solaris is below:

There’s never been a time when I wasn’t collecting... something. Baseball cards, Star Wars figures, Smurfs, Kennedy half-dollar pieces—all were the subject of substantial, deeply felt, slightly random assemblages begun and ended before I was 12. At 13, I got into posters and that was that. At 23, newly minted in Los Angeles with a job ‘close’ to the movie business, I became a weekend dealer of movie posters.

American poster designers such as Saul Bass and Jacques Kapralik, Frenchmen Jean-Michel Folon and Boris Grinsson, Italians Ercole Brini and Ermanno Iaia, among others, framed a new way of looking at art and film and the relationship between the two. But it was a MoMA exhibition catalog of the work of brothers Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg that introduced me to the use of non-objective forms, Constructivism, the Russian avant-garde, all serving a writer’s script and a director’s vision. For me, life expanded.

My personal history with paper, ephemera, and memorabilia is also tied up in my connection to the Soviet Union. I was conceived in Moscow, but born in Ohio. That duality has often become the subject of my work as a visual artist—one foot in each of two very different worlds, two very different streams of history.

In many ways, the very definition of what a poster is and could be was utilized masterfully by the Bolsheviks. They recognized the poster as both an iconic weapon of power and as a traveling propaganda tool.

By repurposing well-known and rare Soviet posters, Solaris attempts to evoke a very specific and simple metaphor: that among the many false representations of his failed revolution, Lenin promised the sun and everything under it—and delivered nothing.

Later, the Communists perfected the art of agitating mass culture by means of multiplying their message. All art had to serve the State and the ideal of their utopia was symbolized by remaking the sun (and its worship) into a logo of sorts. By removing almost all figurative elements, all traces of text, all which is ‘happy’, all that is left are empty, minimal, and absent images. These new works evoke a sense of ambivalence and incongruity, something unfin- ished, and something unsaid.

Moreover, 2017 marked the centennial of Russia’s October Revolution and it just felt ‘timely’ to embark on a series that touches on themes of violence, migration, displacement, disinformation—all the while ironically seeming pretty to look at and ready-to-hang.

As a collector, I lost count of the tens of thousands of posters that were considered as possible raw material for the project. Concerning the assemblage presented in these pages, I’m especially struck by the objectification and commodification of an ideology, which 100 years removed, now becomes a decorative thing to put on one’s wall. There’s a contemporary antiquity to it all. At the same time, there’s an uneasy recognition of history repeating itself.

Published in tandem with the opening of Current Books at Studio Two Three in Richmond, Virginia, this 16 page project-specific monograph, (the artist’s first), features 30 full color images and an essay by Mark Kelner. Printed in an edition of only 200 copies, this catalog is being sold exclusively here. An excerpt from Solaris is below:

There’s never been a time when I wasn’t collecting... something. Baseball cards, Star Wars figures, Smurfs, Kennedy half-dollar pieces—all were the subject of substantial, deeply felt, slightly random assemblages begun and ended before I was 12. At 13, I got into posters and that was that. At 23, newly minted in Los Angeles with a job ‘close’ to the movie business, I became a weekend dealer of movie posters.

American poster designers such as Saul Bass and Jacques Kapralik, Frenchmen Jean-Michel Folon and Boris Grinsson, Italians Ercole Brini and Ermanno Iaia, among others, framed a new way of looking at art and film and the relationship between the two. But it was a MoMA exhibition catalog of the work of brothers Vladimir and Georgii Stenberg that introduced me to the use of non-objective forms, Constructivism, the Russian avant-garde, all serving a writer’s script and a director’s vision. For me, life expanded.

My personal history with paper, ephemera, and memorabilia is also tied up in my connection to the Soviet Union. I was conceived in Moscow, but born in Ohio. That duality has often become the subject of my work as a visual artist—one foot in each of two very different worlds, two very different streams of history.

In many ways, the very definition of what a poster is and could be was utilized masterfully by the Bolsheviks. They recognized the poster as both an iconic weapon of power and as a traveling propaganda tool.

By repurposing well-known and rare Soviet posters, Solaris attempts to evoke a very specific and simple metaphor: that among the many false representations of his failed revolution, Lenin promised the sun and everything under it—and delivered nothing.

Later, the Communists perfected the art of agitating mass culture by means of multiplying their message. All art had to serve the State and the ideal of their utopia was symbolized by remaking the sun (and its worship) into a logo of sorts. By removing almost all figurative elements, all traces of text, all which is ‘happy’, all that is left are empty, minimal, and absent images. These new works evoke a sense of ambivalence and incongruity, something unfin- ished, and something unsaid.

Moreover, 2017 marked the centennial of Russia’s October Revolution and it just felt ‘timely’ to embark on a series that touches on themes of violence, migration, displacement, disinformation—all the while ironically seeming pretty to look at and ready-to-hang.

As a collector, I lost count of the tens of thousands of posters that were considered as possible raw material for the project. Concerning the assemblage presented in these pages, I’m especially struck by the objectification and commodification of an ideology, which 100 years removed, now becomes a decorative thing to put on one’s wall. There’s a contemporary antiquity to it all. At the same time, there’s an uneasy recognition of history repeating itself.